BWC probes seldom find wrongdoing

12/17/2006

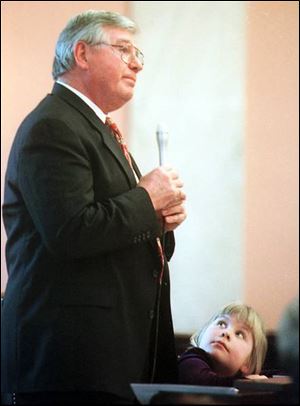

Former Ohio Gov. George Voinovich and Gov. Bob Taft chat at a meeting in 2001.

COLUMBUS Bonnie Fraser was working in her office in a Cleveland suburb when the phone rang earlier this year. Samuel G. Lucarelli was on the line.

She had met with the head of Cleveland s influential Lucarelli family earlier in the day at his office headquarters downtown.

Ms. Fraser, whose firm represents companies in workers compensation cases, said Mr. Lucarelli had a simple proposition for her. Refer her clients to his son s company 1-888-OhioComp and he d make sure she received 10 percent of the money the companies generated for 1-888-OhioComp from the Ohio Bureau of Workers Compensation.

She could take the cash quarterly or once a year.

In a recent interview, Ms. Fraser said she considered Mr. Lucarelli s offer to be a bribe but later learned that kickback would be a more precise term.

After a second call a few days later, she said she turned him down. He could not understand why I wasn t jumping at the chance.

Mr. Lucarelli, convicted in 1989 of racketeering stemming from an illegal gambling and loan-sharking operation in Cleveland, said last week that he does not recall talking to Ms. Fraser earlier this year, let alone offering her cash for the business she could bring to his son s business.

Your problem is with the bureau call them and get the answers from them, he said.

Ms. Fraser said she met with Mr. Lucarelli at his office for about two and a half hours.

He told me he was in semiretirement in Florida, but they bring him back here every two years for open-enrollment, she said.

Ms. Fraser, president of ActuComp, an Avon Lake company, is considered by state officials as a third-party administrator.

The Lucarellis 1-888-OhioComp is a managed-care organization based in Cleveland. It is among dozens of firms that receive millions of dollars each year from the workers compensation bureau for managing the care of Ohio s injured workers.

The money is paid to the managed-care firm by the bureau, but it comes from premiums paid by Ohio businesses based on the size of their work force and the number of injured workers they have each year.

Managed-care firms such as 1-888-OhioComp and dozens of others approved by the bureau are in competition to lure as many businesses as possible to their firms. The more businesses they have, the more injured workers under their care, and the more money they make from the workers compensation bureau.

State regulations prohibit managed-care firms from offering money to third-party administrators such as Ms. Fraser in return for client referrals.

A managed-care firm can be decertified or its contract terminated with the bureau for violating the rules.

Since early 2004, the bureau has investigated at least 30 allegations of kickbacks or improper marketing in its managed-care operation, a Blade investigation has found.

A review of the cases showed the investigations unit examined the claims with little vigor and quickly rejected the allegations or deemed them unfounded.

Only once did the bureau substantiate an allegation and punish a managed-care organization for improper marketing. The firm was not allowed to accept new employers for three months.

Scott Fitzgerald, an assistant director in the bureau s special investigations department, said the bureau receives up to 6,000 allegations a year mostly about workers claiming injuries and tries to work through its cases as efficiently as possible. He said if agents can t substantiate an allegation, We usually don t move forward with it.

That s what happened when Ms. Fraser told the bureau about Mr. Lucarelli s offer.

Bureau records concerning her complaint about Mr. Lucarelli are consistent with what she told The Blade.

She said he offered her a 10 percent commission for every client she can get them, the bureau s investigative report stated He said he would pay her quarterly or yearly, whichever she preferred.

Ms. Fraser said she called the bureau to find out if it was illegal to take money from a managed-care organization for steering them clients.

A bureau investigator interviewed her, but bureau records do not indicate that investigators talked to Mr. Lucarelli. Records show state investigators did interview his son, Jay Lucarelli, CEO of 1-888-OhioComp.

He told them that neither he nor his father offered Fraser any money.

The investigators concluded that they were unable to substantiate that any bureau rules were violated. The bureau promptly closed the case without further action.

Apparently, they don t want to investigate this for some reason, Ms. Fraser said. They don t want to turn over the rocks, and that is not a good thing.

A history of secrecy

The bureau under fire for the past 20 months because of corruption in its investment department and accusations of waste in its managed care program has a disturbing history of secrecy and a failure to police itself, said state Sen. Marc Dann, a Democrat who becomes Ohio s attorney general next month.

The problems are rooted in the administration of former Republican Gov. George Voinovich who trashed the bureau in his 1990 gubernatorial campaign as the silent killer of jobs and then used it to pump money into the state GOP machine, Mr. Dann said.

Chris Paulitz, a spokesman for Mr. Voinovich, now a U.S. senator from Ohio, said last week that the senator is extremely proud of his legacy of helping injured workers as governor. Mr. Paulitz said his legacy includes leaving a $3.5 billion surplus when he left the governor s office in 1999.

Former Ohio Gov. George Voinovich and Gov. Bob Taft chat at a meeting in 2001.

Gov. Bob Taft inherited the bureau s management as well as the campaign cash received from the executives and owners of firms doing business with the agency.

Records show the Lucarelli family, its executives, and the heads of other managed-care firms have contributed hundreds of thousands of dollars to the campaigns of top state officeholders, including Mr. Taft s.

Mr. Taft declined to grant a year-end interview with The Blade and declined an interview to discuss problems at the workers compensation bureau.

The interview would focus on the BWC and everything and not get into what he has accomplished and the positive impact he has had on the state, said Mark Rickel, the governor s press secretary.

The bureau also refused to make Bill Mabe, its administrator-CEO, available for an interview.

Bureau spokesman Nancy Smeltzer contends the agency, at this moment in time, is more transparent than ever.

Ohio s workers compensation system is governed by a complex set of rules and regulations, designed by lawmakers and the agency s oversight commission to prevent fraud, corruption, undue influence, and to protect injured workers and businesses.

The agency has its own investigations unit that is charged with probing allegations of fraud or wrongdoing within the system or by those doing business on behalf of the system.

Unfounded cases

Ms. Fraser, who told the bureau about being offered money by Samuel G. Lucarelli, said she also was offered a 5 percent commission a few years earlier by an executive from another managed-care organization, but she turned that offer down as well.

She said when she began to send her clients to a third managed-care organization, a company official asked her: You are referring business; what do you want?

Ms. Fraser s complaint about kickbacks have not been the only one the bureau s investigative unit has received.

In fact, earlier this year officials from the Lucarellis 1-888-OhioComp alleged that a competitor, Gates McDonald Health Plus, offered a kickback to the city of Cleveland in exchange for enrolling with its firm.

Documents obtained by The Blade show that bureau fraud agents never called Gates McDonald about the claim and stopped pursuing the issue after Barry Withers, a special assistant to Democratic Cleveland Mayor Frank Jackson, denied the city was offered any money from a managed-care organization.

The case was closed as unfounded.

Two years earlier, in May, 2004, the bureau received two allegations that employees of managed-care organizations had offered special discounts to businesses that picked their firms or referred clients.

In one case, Duane Szymanski of CorVel, a managed-care organization, accused officials from CompManagement of offering a discount to an employer who signed up with both their managed-care organization and third-party administration service.

Bureau agents contacted one employer who had been named in the allegation, and the business denied it had received any special benefit to sign up with CompManagement s managed-care organization. The bureau two days after opening the case and without further investigation deemed the allegation unfounded.

At the same time, bureau officials looked into an allegation that CorVel was hiring employees of third-party administrators so they would refer employers to CorVel.

Bureau investigators contacted the third-party firm named in the allegation and two marketers for CorVel. All denied that kickbacks were being given. The bureau closed its case.

Mr. Dann, the Democratic attorney general-elect who campaigned on the promise to root out corruption in the bureau, said last week: We re going to look at every aspect of the conduct of business at BWC.

Mr. Dann also said the attorney general s office plans to examine the bureau s operations for possible criminal charges.

There are a wealth of issues there and this is another one, Mr. Dann said.

A pattern of trouble

During the past decade, the bureau on a number of occasions has failed to satisfactorily investigate itself or failed to disclose public information when confronted with allegations of wrongdoing:

Noe

• In April, 2005, when The Blade began publishing a series of stories about the agency s $50 million rare-coin venture with GOP fund-raiser Tom Noe, bureau officials vehemently defended Noe and unleashed a counteroffensive against the reports despite having knowledge that its own internal auditor in 2000 had raised serious concerns about money and coins missing from the Noe coin funds.

The bureau also refused to release inventory records of the coin fund investments until ordered to do so by the Ohio Supreme Court after The Blade sued the bureau.

Noe is serving an 18-year prison sentence for stealing millions from the coin fund.

Gasper

• A 1997 internal probe at the agency examined allegations that Terrence Gasper, the bureau s chief financial officer, schemed to favor certain investment brokers. The investigation found no wrongdoing, but earlier this year Gasper pleaded guilty to taking bribes from brokers and marketers doing business with the bureau. He is set to be sentenced in federal and state courts later this month.

• In the days leading up to the 2004 presidential election, e-mails show bureau officials worked to keep secret a $215 million investment loss in a Bermuda-based hedge-fund. The losses weren t disclosed until the summer of 2005, amid the broader investment scandal spurred by the investigation into the Noe coin funds.

• Last week, the bureau announced it would reduce the amount it pays to managed-care companies after a Blade investigation revealed that several politically connected firms, including Dublin-based CareWorks and the Lucarelli s 1-888-OhioComp, had collected millions of dollars from the agency while pouring thousands into the campaign coffers of the state s top elected officials including Senator Voinovich, Governor Taft, and Gov.-Elect Ted Strickland, a Democrat.

The bureau s CEO, Mr. Mabe, told the agency s oversight commission last week that the change would save the agency about $17 million a year.

Friends of the bureau

The bureau s failure to fully investigate allegations of fraud and mismanagement in its managed-care program doesn t surprise some former employees.

When E. Roberta Wade read in October, 2005, that a bureau official had referred to Mark D. Lay the head of the firm that lost $215 million for the bureau in hedge funds as a friend of the bureau, the phrase was a familiar one.

In the early 1990s, Ms. Wade was the supervisor of the bureau s regional claims office in Mansfield. She said she twice stopped a bureau official, John Finch, from processing a claim on behalf of an injured worker who had received the maximum amount of benefits.

Ms. Wade said when she asked a bureau employee why Mr. Finch was pushing the issue, the response was: It s a friend of the bureau.

I didn t understand what that meant then. Now I see it as a sign that the fix is being put in from the top down, said Ms. Wade, an attorney.

She said she sent certified letters to Republican state Auditor Jim Petro, then-Governor Voinovich, and James Conrad, the bureau s administrator-CEO, telling them that her office never was audited. She said she never received a reply.

An investigation by then-Inspector General Richard Ward found that after Ms. Wade stopped the claims processed by Mr. Finch, the bureau apparently retaliated by starting an internal investigation into her office.

High-ranking bureau officials asked her to resign and presented her with a document in which she would promise to no longer make negative comments about the bureau in exchange for a neutral job reference, the inspector general s investigation found.

Ms. Wade didn t resign, but the bureau fired her in 1994.

Because of the bureau s problems, Mr. Ward recommended that the bureau consider hiring its own anti-corruption watchdog that would be independent of the agency s legal and investigative-audit division, a recommendation that was never followed.

Commenting on the allegations from Ms. Wade and others about wrongdoing at the bureau, Mr. Ward wrote: They are symptomatic of a large agency comprised of many individuals who have competing interests of pursuing personal career advancement, of assigning blame and finding fault, of playing office politics, and settling petty disputes arising from personality conflicts.

These interests sometimes conflict with the larger goal of working together to serving the injured workers of Ohio. They are considerations which must be set aside in order for BWC to work effectively, he added.

Ms. Wade said the bureau did not follow Mr. Ward s recommendations.

They re really good at covering things up, she said, adding that all changed when the Tom Noe rare-coin scandal broke.

The former stepchild

In the decades before Mr. Voinovich became governor in 1991, the bureau was among the state s most troubled agencies, considered a dumping ground for political hacks and jammed full of paper-pushers.

It was the stepchild of state government, said Mary Anne Sharkey, a former Statehouse reporter who was Mr. Taft s communications director during his first term.

Mr. Voinovich and his successor, Mr. Taft, have delivered chest-thumping speeches proclaiming that they replaced Ohio s silent killer of jobs with a fiscally sound bureau with solid investments and an efficient medical operation.

Both governors trumpeted the bureau s achievements, including dividends for Ohio s employers, double-digit investment returns, and the implementation of drug-free workplace programs.

But the bureau also became a political money machine for Mr. Voinovich, Mr. Taft, and the Ohio Republican Party a tool to help them finance elections, with multimillion-dollar bureau contracts going to political contributors and political supporters such as Tom Noe. Noe was not only one of the state GOP s best fund-raisers, but designated a Pioneer for raising at least $100,000 for President Bush s re-election campaign.

Mr. Voinovich appointed James Conrad, one of his most trusted aides, to run the bureau in 1995, and Mr. Conrad was Mr. Taft s first appointment when he became governor.

Dubbed Mr. Fix-it, Mr. Conrad was the man Mr. Voinovich would turn to when he cited the bureau as an example of his administration s successes.

Mr. Voinovich, Mr. Taft, and Mr. Conrad all understood that the bureau s image was central to their political fortunes.

Taft spokesman Mark Rickel, speaking on the governor s behalf last week, said: As long as the bureau is a state agency, there will be some aspect of politics. If it were privatized, in theory politics would be minimized, but the proof would be in the pudding.

Asked if the agency s troubles are rooted in its concern with its image, Mr. Voinovich s spokesman, Mr. Paulitz said: As he has always said, if someone did wrong at the BWC or anywhere else, then let justice be served.

Problems surface

In July, 2004, Mr. Conrad declined to pursue an opportunity to head the Ohio Department of Job and Family Services. Among the reasons was he didn t want to leave the bureau, Mr. Conrad explained in an e-mail at the time, was that BWC can take front stage in the media fairly quickly if mishandled.

Less than a year later, the bureau was at the center of a scandal over its $50 million investment in rare coins. The scandal, which led to Mr. Conrad s resignation and criminal charges filed against 14 people including Governor Taft for not reporting gifts he accepted from Noe exposed the bureau s culture of secrecy and self-promotion.

The most glaring example was that, despite warnings, Mr. Conrad and other politically appointed bureau officials stood by for seven years as Noe stole more than $13 million from the bureau s rare-coin investment. The bureau s leadership refused to seriously address concerns raised by bureau auditor Keith Elliott about the coin funds and ignored him when he suggested the agency should end its venture with Noe.

When Mr. Elliott wanted to look into a misappropriation of assets from the coin funds in September, 2004, Mr. Conrad reacted by trying to protect the bureau s image. In an e-mail, he instructed two of his high-ranking underlings to stay on this, adding, You know Keith s biases on this account.

When The Blade first reported on the problems with the coin venture in April, 2005, Mr. Conrad fiercely worked to blunt the newspaper s reports by issuing statements, letters, and news releases to spin a position message about what he claimed was a high-performing investment. And, Jon Allison, Mr. Taft s chief of staff, was quickly onboard for the counteroffensive, issuing directives to bureau officials about what should be said in the agency s statements and news releases.

During the past few weeks, we ve gone to great lengths to be forthcoming with you and refute the points The Blade has produced, Mr. Conrad wrote in the memo to the bureau s oversight commission on April 19, 2005. At this point, we feel further communications are not warranted unless they start publishing real, factual stories.

Former State Rep. Ross Boggs called for an investigation of the BWC s investment practices in 1997.

Earlier warnings

In 1997, Ross Boggs, then the highest-ranking Democrat in the Ohio House, predicted that Mr. Voinovich and the Republican leadership would pay a steep price for the takeover and politicization of the bureau.

In a news release at the time, he said Mr. Voinovich and his top aides wanted to get their hands on the BWC fund and that their reforms were not going to help any injured workers.

Governor Voinovich wanted control of the Bureau of Workers Compensation so he could continue to reward his big business campaign contributors, Mr. Boggs statement read. You know the old adage. Be careful what you wish for Governor. You just might get it.

Mr. Boggs at the time called for an investigation by the inspector general into the bureau s investment practices after accusations that Mr. Voinovich funneled half of the bureau s bond sales to KeyCorp, which employed one of his high-ranking former appointees. An investigation never took place.

Reached last week, Mr. Boggs said the bureau s investment scandal made him recall his opposition to Mr. Voinovich s takeover of the bureau.

It was too late to say, I told you so, but that s what happened, said Mr. Boggs, now retired and living in Andover, Ohio, east of Cleveland. It s nice when your political party has everything, but it gets you into a trouble a lot of times. You ve got to have checks and balances in our political system.

Contact Steve Eder at: seder@theblade.com or 419-724-6272.